Squeeky, The Golden Voice Thrower By Gary R. Brown

In an unsuccessful attempt to acquire the most coveted, albeit useless, ventriloquism gizmo of the 20th Century, I inadvertently unearthed a deeper, darker and far more dangerous ventriloquial secret. Ironically, though as ineffective as the original object of my search, this newly uncloaked gimmick bears the imprimatur of the United States Patent and Trademark Office, attesting to its utility . . . more or less.

Readers of a certain age may recall advertisements for a device called “The Ventrilo,” which promoters crammed into the pages of comic books, novelty catalogs, Popular Mechanics and Boys’ Life in the 1960s and 1970s, alongside offers for X‐Ray Specs, Sea Monkeys and the “U‐Control 7 Foot Ghost.” The Ventrilo promised the ability to “Throw Your Voice” and “fool teachers and friends” with an “instrument [that] fits in your mouth and out of sight.” Usually, the ad copy featured a disembodied voice calling for help, seemingly emanating from a trunk toted by a muscular fellow, but really being “thrown” by a smirking, smart‐alecky kid standing nearby. Recently, collector Kirk Demarais showcased The Ventrilo amid vintage miscellany in his fabulous book, Mail‐Order Mysteries: Real Stuff from Old Comic Book Ads!, a particular joy for those who were prevented, by circumstance or parental regulation, from allocating their allowance to accumulate these sought‐after sensations.

As Demarais reveals, readers enticed by the unbridled powers of ventriloquism into sending off the requisite two bits received

The Ventrilo, a kazoo‐like device which he describes as “two half‐inch metal pieces bound by a pink ribbon.” The accompanying

instructions hastily retreat from the lofty advertising claims. “While you do not need the Wonder Ventrilo or other device to be a Ventriloquist, it will help you decide whether you would like to learn more about Ventriloquism.” Unquestionably, designers modelled The Ventrilo on the swazzle or Punch whistle, a device utilized by Punch & Judy operators to infuse Punch’s falsetto voice with a raspy quality and to introduce sundry sound effects. Skilled puppeteers secreted the swazzle in their mouths, moving it into position between the tongue and the palette as needed. Traditionally, puppeteers considered the gimmick a closely‐guarded trade secret. Comic book claims aside, however, a Punch whistle won’t help you throw your voice.

I first encountered the Punch whistle while researching Al Flosso’s life for The Coney Island Fakir. Flosso, an accomplished Punch & Judy performer, employed a silver Punch whistle during puppet shows, and to emit startling rasps during his Miser’s Dream act. More relevant here, though, was his production of

cheap Punch whistles as part of a carnival side‐show pitch act. Bill Tarr recalled Flosso employing a pair of tin snips “like a machine” to mass produce Punch whistles from metal cigar containers. The pieces were strung with tape and then wrapped in cloth or elastic. Another accomplished puppeteer, Jay Marshall, suggested than anyone trying to use these items would “probably cut his throat.” Thus, The Ventrilo has a storied history both as an appliance used by professional puppeteers and as a low‐quality pitch item foisted upon unwary purchasers.

With my interest rekindled by Mail Order Mysteries, I happened upon an eBay lot listed only as a “Magician’s Junk Drawer,” comprising material amassed by a magic enthusiast from Boise. Among the accumulated detritus depicted in the photos was, to my great delight, an envelope apparently containing The Ventrilo, and the auction description assured me that there was a ventriloquial gaff inside. The sole bidder, I won the lot for $10 plus postage, which soon shipped directly from Idaho. Excitedly, I opened the box, culled through the flotsam (which included actual garbage) to extract my prize. In the great tradition of purchasers being disappointed by such acquisitions, the envelope contained a set of instructions, but, alas, no Ventrilo. My childhood dreams of acoustic deception were, once again, shattered.

Just then, deep inside the envelope, I discovered two smaller packets purporting to contain two different voice throwing appurtenances. The first, called “The Golden Voice Thrower,” sported a line drawing reminiscent of those used to promote The Ventrilo: a bellboy lugging a trunk flummoxed by voice‐throwing wisenheimer. (Upon reflection, it is notable how often amateur ventriloquists of that era encountered trunk‐hefting fellows.)

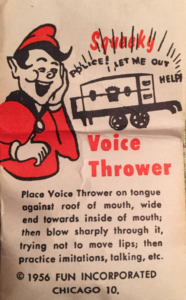

The second, called the “Squeeky Voice Thrower” featured substantially more imaginative artwork: a two‐color drawing of an elven character projecting his voice into yet another steamer trunk – this one borne on a wheeled cart. The packages were labelled with identical instructions for the device contained inside: “Place Voice Thrower on tongue against roof of mouth, wide end toward inside of mouth; then blow sharply through it, trying not to move lips; then practice imitations, talking, etc.” Sounded fairly straightforward and easily committed to memory.

So I plunged in. That the Golden and Squeeky Voice Throwers turned out to be different monikers for the very same appliance would prove the least of the dissatisfactions that would follow.

The Golden/Squeeky Voice Thrower consists of a tiny, barrel‐shaped, metallic contraption approximately the size and shape of an aglet (found at the end of a shoelace), with a miniscule reed embedded inside. Visual and magnetic inspection suggests that the gaff is composed mainly of lead. If The Ventrilo, as some have observed, represents a choking hazard, the Squeeky constitutes a choking certainty. While this intrepid investigator unhesitatingly gambled a sawbuck in pursuit of this story, risking an emergency room visit by following the directions on the package was not in the cards. However, a more limited test – clutching the device firmly between thumb and index finger and pressing it against tightly perched lips – revealed the that the Golden Voice Thrower can produce a shrill whistle, annoying to nearby humans but of great interest to my dog.

Puzzlingly, a minute US patent number had been embossed on the barrel of the voice thrower. Under federal law, the grant of letters patent by the United States Patent and Trademark Office demands that an inventor prove that the subject invention is, among other things, novel and useful. Patent examiners regularly and notoriously reject applications for devices determined to be inoperable ‐‐ otherwise patents would issue for fanciful or theoretical concepts like perpetual motion machines or cold fusion generators. And given that these voice throwers are indisputably useless, how could the USPTO grant anyone the exclusive right to dabble in such futility? While a search of the USPTO database for “voice throwers” did not turn up any results, a search of the specific patent number proved enlightening. Issued in 1952, Patent Number 2,590,743, entitled “Sound Maker for Toys and Other Devices,” does not describe an aid for ventriloquists but rather an inexpensive metal device to be inserted into “rubber dolls and toy animals.”

In addition to being “compact and rugged,” these squeakers feature “spring tension . . . to provide a permanent force for keeping the sound maker in position” when mechanically inserted into a manufactured squeaky toy. The idea was to keep the squeaker in the toy and out of the human mouth. Yet the purveyors of the Squeeky Voice Thrower not only sold these contrivances liberated from any kind of toy, but actually instructed users to keep the item perched atop the tongue while trying to do imitations.

Chicago‐based magic manufacturer Fun, Inc. packaged these units and applied for a copyright on the Squeeky artwork in 1956.

Distribution seems to have fallen to an obscure outfit called Manhattan Playthings, Inc. which, not coincidentally, shared the Broadway mailing address of Mike Tannen’s Circle Magic Shop. Manhattan Playthings hawked these items directly to carnival pitchmen for nine dollars a gross (or about six cents apiece) through splashy display ads in Billboard magazine the following year. “Fast Selling! Sure Fire! Quick Catching Novelty!” the ads exhort, unbridled in the use of superlatives and exclamation points, “Sensational! New! Different!” Laden with falsehoods, the ad copy claims that the gadget which “Mystifies” and “Baffles!” would “enable any person to project his voice” and, most notably “Fool your friends.”

Of course, the only people ever fooled by a voice thrower were those who bought one. The unidentified Idahoan Man of Mystery numbers among the deceived, having procured The Ventrilo and both iterations of the Squeeky/Golden scam, likely disbursing seventy‐five cents for the privilege. The same can be said, embarrassingly enough, about your correspondent, except I spent twenty times that sum and countless hours researching their history.

Gary R. Brown is a magic writer, whose work includes The Coney Island Fakir: The Magical Life of Al Flosso, and a U.S. Magistrate Judge. Judge Brown has bequeathed his recently‐acquired collection of intraoral voice throwers to the Conjuring Arts Research Center, “so that they may be examined and debated by scholars and historians throughout the coming centuries.”